Introduction

I read Project Hail Mary upon a recommendation from a friend. I had read Andy Weir's The Martian some years ago and enjoyed it, so I decided to give his third book a read (at time of writing, I have not yet read his second book, Artemis).

I found the book to be similar to his first, at least at a high level. Both novels are in the hard sci-fi genre, with an abundance of scientific detail and justification provided. Both tales are also about resourceful and likeable space-faring protagonists who spend a considerable portion of the book in isolation, with their inner monologue therefore driving much of the narration. Both books also contain elements of optimism regarding humanity and its virtues, and inject a healthy dose of humor throughout.

Yet, the premises of the books are quite different. In Project Hail Mary, the protagonist, Ryland Grace, has set sail for a destination much further away than Mars – another solar system entirely – as part of a mission to save Earth from an alien species that is depleting the Sun of its energy.

On his mission, Grace encounters a being from yet another species which he dubs the 'Eridians'. These beings resemble large, pyramidal arachnids without eyes, mouths, or noses. Unlike many other sci-fi books, and by virtue of being in the hard sci-fi genre, the book attempts to explain various traits of the species and how they could have conceivably emerged as a result of Darwinian forces.

In my last Bookish post, I wrote about another alien civilization. I find these books interesting because they encourage us to eschew the anthropic lens through which we usually view the world. By contrasting our species with another, we are forced to grapple with fundamental questions about our own kind, and why things are the way they are.

Speech & Language

One consequence of Eridian biology is that they lack "sight", at least as defined in the usual human sense of having biological machinery that perceives photons of varying wavelengths and translates them into visual imagery. In order to compensate, an Eridian's auditory faculties are far more sophisticated than that of a human, and they rely on sonar in order to "see".

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Eridians too evolved the ability to communicate via auditory language. In Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, Yuval Noah Harari postulates that language is a distinguishing ability of humankind that has allowed us to cooperate at large scales and establish civilizations. If this theory is correct, why shouldn't we expect other intelligent species to independently evolve the ability to communicate via language?

'Eridianese' is similar to human language in some ways. For example, Eridianese has an alphabet: a finite set of elements which can be composed together in order to construct words, which can be further composed in order to construct sentences, and so on. In this sense, the alphabet is an atomic building block for language. An element of the alphabet itself rarely conveys any meaning; a word is greater than the sum of its parts.

However, the Eridianese alphabet is quite different from Latin or Chinese ones when it comes to speech. In order to pronounce different elements of most human alphabets, we vary the place and manner of articulation1. Further, few human languages utilize pitch to represent elements of the alphabet. Indeed, Mandarin possesses tones, though these rely on relative pitches as opposed to absolute ones. In direct contrast, the Eridianese alphabet is absolute pitch itself (modulo octaves), with the place and manner of articulation having seemingly no bearing. More precisely, the alphabet consists of chords of notes, since Eridians have the ability to "pronounce" multiple notes at once.

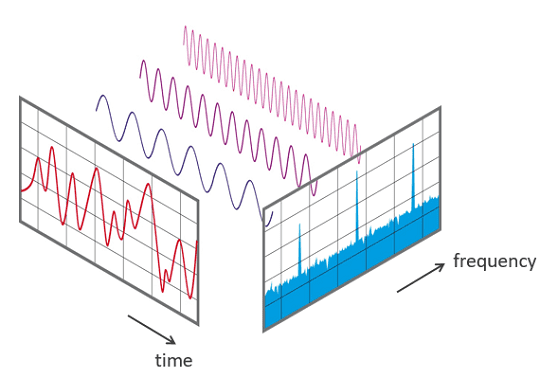

This happens to make speech-to-text shockingly easy to compute. Grace wields

some simple Fourier transform

software in order to decompose chords into their constituent notes, and then

catalogs their meaning in a spreadsheet. With a VLOOKUP query, Grace is able

to build a Eridianese-English dictionary.

Another similarity between spoken Eridianese and human languages are that they occupy roughly the same frequency ranges. Considering the full spectrum of frequency ranges, it's hard to imagine this would be a coincidence. Why don't Eridians vocalize at extremely high or low frequencies, inaudible to human beings? The answer proposed in the book is that certain sounds, like the one made by objects colliding, have the same frequency universally. Natural selection would therefore favor those who could hear the sound of hooves pushing against the dirt, or of leaves rustling in a nearby bush, in order to protect themselves against potential predators. If our auditory faculties evolved to perceive these narrow frequency ranges, why should our spoken word occupy another?

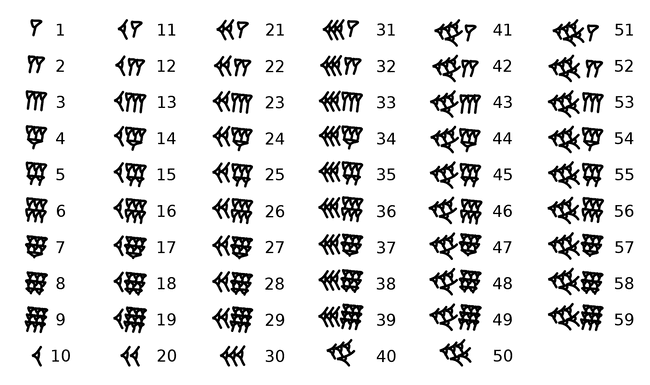

Number Systems

In addition to evolving language, Eridians evolved a number system not unlike our own. Although this isn't explained in the book, one could imagine how Darwinian forces would favor those who can construct and communicate natural numbers. The being who can count apples can determine which tree is most worth climbing, in order to preserve the most energy while reaping the largest reward. The being who can count bodies can determine whether they are outnumbered when they encounter a rival tribe, in order to make a fight or flight decision.

The Eridian number system is different from ours in two primary ways: its symbology and its radix. The former is not surprising: after all, different human languages use different symbols for the natural numbers. The latter is not all that surprising either: some ancient human civilizations used base-60 number systems as opposed to the decimal system with which we are familiar.

In the book, Grace rationalizes the Eridians' use of a base-6 number system using the same argument for why humans use a base-10 system: each Eridian "hand" contains 3 digits, so two "hands" would be able to count to 6. However, Eridians have 5 such "hands" – why do they not use a base-15 number system instead? Like 6, 15 is semiprime. However, unlike 15, 6 is a superior highly composite number, which lends itself well as a useful radix. Perhaps some ancient Eridian civilization used a base-15 number system, but they eventually switched to the base-6 system for its merits. 12 is the next largest SHCN, which is one of the reasons why many argue that a base-12 number system would have been more useful than the base-10 number system we use.

Intelligence

During one of their discussions, the Eridian poses the following question to Grace.

“Better question,” he says. “Why we think same speed, question?”

I shift over to lie on my side. “We don’t think at the same speed. You do math way faster than I can. And you can remember things perfectly. Humans can’t do that. Eridians are smarter.”

He grabs a new tool with his free hand and gets back to tinkering. “Math is not thinking. Math is procedure. Memory is not thinking. Memory is storage. Thinking is thinking. Problem, solution. You and me think same speed. Why, question?”

The Eridian seems to believe that the ability to follow procedural instructions and the capacity for memory are insufficient ingredients for "thought". I was reminded of the Ant Fugue from Douglas Hofstadter's [_Gödel, Escher, Bach]. In this chapter, we learn about "Aunt Hillary", an entity observed to have thought and demonstrate intelligence and consciousness. However, Aunt Hillary is not a single being, but rather a colony of ants, each of which seemingly lack intelligence. Consciousness is seemingly greater than the sum of its parts. It is an emergent feature, without explicit definition.

Computers can be aptly described as entities that follow procedural instructions with the capacity for memory. Do they lack thought? Do they lack intelligence? This is indeed one of the fundamental philosophical questions in the field of artificial intelligence and computer science more broadly.

Although I disagree with the Eridian's argument that math and memory are not sufficient for defining "thought", I can see its appeal. Math and memory can be encoded as formal systems. Computation can, as well2. When we define a formal system, it seemingly loses its mystery, in the same way that the explanation of a magic trick robs it of its wonder. As humans, we'd like to think we're special. We'd like to think our intelligence and consciousness can't be fully captured by symbols and syntax. So, even a novel attempting to break the shackles of our anthropic worldview can't help but let some leak through.

Footnotes

- There's a great video by Tom Scott on this topic. ↩

- In fact, there are many formal systems for describing computation, including the Turing model and its variants, the lambda calculus and its variants, the pi calculus and its variants, and so on. ↩